China builds giant air conditioner cooling almost 3 square kilometres

Shenzhen has just finished building an instalment of a central District Cooling System (DCS), which supplies cold air to malls, offices and transport stations.

The company which built the system, the Shenzhen Qianhai Energy Technology Development Company, is also working with Hong Kong on a DCS located in Kai Tak.

The No. 5 cooling station, which started supplying cold air in June in Shenzhen’s Qianhai area, covers more than 2.75 square kilometres of public buildings, but not residential households.

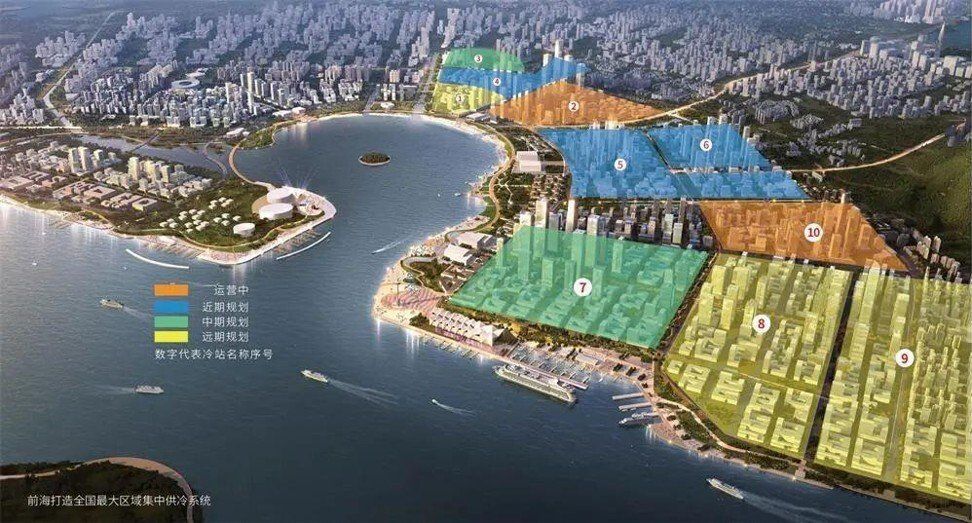

This image shows how the various stages of the project will bring cooling to the city.

This image shows how the various stages of the project will bring cooling to the city.

“The characteristics of residential households determine that they are not suitable for DCS, the system calls for more routine usage, such as from eight to five, that includes offices, commercial centres, subways or data centres,” said Fu Jianping, director of Qianhai energy and vice-president of the District Energy Committee of the China Association of Building Energy Efficiency.

The station is the newest addition to an elaborate DCS in Qianhai, a free trade and economic development area. Currently, three stations have been finished, including No. 5, and seven more will be built over the next few years.

When finished, the 10 stations, with the investment of about 4 billion yuan (US$617 million), can supply a total of 400,000 Refrigeration Ton (RT) of cold air, covering 19 million square metres.

Shenzhen first started planning the DCS alongside Qianhai’s development in 2014. The government analysed Qianhai’s energy needs and decided that in southern China, air conditioning is a major consumer of energy, Fu said.

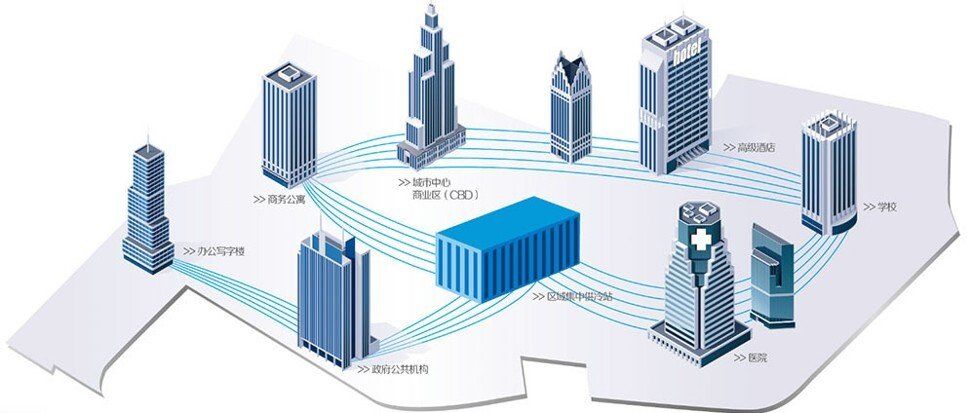

A DCS distributes cooling capacity in the form of chilled water or other medium from a central source to multiple buildings through a network of underground pipes. At the DCS station, which is four floors underground, the South China Morning Post saw a tangle of pipes, water collectors, separators and coolers in an area vast enough for a football field.

“It’s like a factory that has industrialised production of chilled water for an air-conditioner,” Fu said.

The plans for Shenzhen in China to build a giant air conditioner cooling

almost 3 square kilometres of public buildings to reduce energy

consumption.

The plans for Shenzhen in China to build a giant air conditioner cooling

almost 3 square kilometres of public buildings to reduce energy

consumption.

He said the system in Qianhai can save 130 million kilowatts of electricity every year, which is equal to burning 16,000 tonnes of coal, reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 130,000 tonnes.

“A DCS is a centralised system so it cuts down machinery by 20 per cent, as opposed to installing individual machines, and the fewer machines, the less refrigerant we use. That’s one way to reduce emissions,” he said.

Furthermore, the company will pay more attention to energy-saving technology and choose more efficient equipment, even if it means more investment.

“This is an energy company, the money we invested will need to see returns in future operations, so the more maximised use I get out of energy the better,” Fu said.

DCS is found in many parts of the world, including Japan, Canada, Middle East, US and parts of Europe, even though techniques and development vary from one country to the next.

In the US, where demand for air-conditioning is one of the highest in the world, large systems were built in the 1930s in Rockefeller Center and the first commercial DCS has been in operation since 1962 in Hartford in Connecticut.

However, the system is not without its shortcomings. Some controversy around DCS includes energy lost when delivered through the pipes and the large investment involved in the system.

Yang Fuqiang, a senior adviser in Beijing for US environmental group the Natural Resources Defence Council, said DCS requires certain conditions to install.

“These stations cannot be too big or too small, but an appropriate economic size. The buildings need to be concentrated, and the pipes need to have good heat preservation,” he said.

In the past, some DCS projects in China were widely questioned. In 2009, local media reported that a project in central China’s Taiyuan could supply one million square metres but in reality only 50,000 square metres was covered and could not operate profitably. Companies and real estate agents were not willing to buy these services because it’s more costly than standard air-conditioning.