Serbia still hasn't come to terms with the 1999 NATO bombing campaign

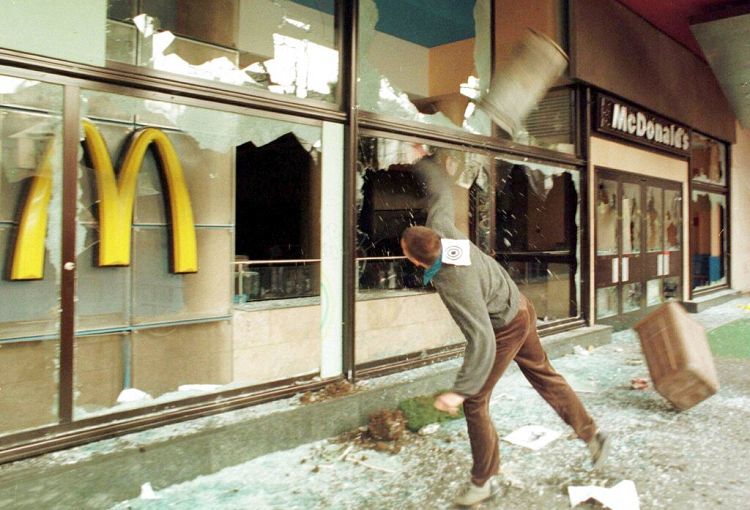

The two-and-a-half-month operation involving major air strikes undoubtedly represents an experience of collective and personal trauma.

And every 24 March — the day the air raids to stop another war-crime-riddled campaign by strongman leader Slobodan Milošević began — Serbs relive their traumas of the last 20 and so years.

Yet, the majority of people in Serbia today see themselves as the only victims of what is referred to as NATO aggression, not intervention.

Kosovo's ethnic Albanians, who were the sole target of Milošević's forces in Serbia's then-province, either do not exist in this narrative, or are perceived as murderous, subhuman puppets of the West.

As this narrative of self-victimisation grew over the years, the space for reflection completely shrank, and the NATO military intervention itself is now viewed as a goal in its own right — an isolated event whose only purpose was to target Serbia and its people.

"This is an integral part of the conspiracy theory that is at the root of the lasting legacy of Milošević’s regime: the West has been out to get Serbia and Serbs in general for centuries."

It wasn’t the result of the systematic policy of repression and disenfranchisement of Kosovar Albanians that had been going on since the end of the 1980s, started by Milošević, one-sidedly diminishing the political autonomy of the province under the control of Belgrade, that ended up in bloodshed.

Not at all. It’s as if the US and the collective West made a secret plan to intervene militarily against the rump Yugoslavia comprising Serbia and Montenegro at the time and invented a reason for it instead.

This is an integral part of the conspiracy theory that is at the root of the lasting legacy of Milošević’s regime: the West has been out to get Serbia and Serbs in general for centuries.

Serbia belongs in Europe, but first, it has to overcome the barriers it built itself

The truth is, however, that there is no concrete historical obstacle or divide that stands in the way of cooperation and even integration of Serbia with the rest of Europe, to which it clearly belongs.

Milošević’s lust for unlimited power, his support for the wars which raged across the former Yugoslav republics, and his rejection of democracy and an open market economy are what built the wall that still separates Serbia from Europe.

It is an artificial barrier constructed by Belgrade’s own erroneous and criminal policies.

"In the end, the type of black-and-white thinking typical of populists everywhere has denied Serbia a shot at a complete catharsis."

While these particular policies ended by 2000 and the removal of Milošević from power by massive protests that saw him end up in front of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague, the narratives his regime hung on to survive to this day.

In fact, they were actively reconstructed and expanded when Serbia’s new undisputed populist leader, Aleksandar Vučić, came to power in 2012.

While Vučić was careful not to repeat the mistakes of his predecessor and engage in direct conflict with the democratic world — he even facilitated cooperation with the EU and NATO alike — he intentionally made Milošević’s narrative of Serbs as the main victims of the Yugoslav wars official state propaganda once more.

In turn, this brought him votes and popular support.

What would ensue is more than a decade of an unrelenting campaign of disinformation in which Serbs have been shown — through newspapers and tabloids, TV channels, films and TV shows, public statements made by officials, faux independent experts and the Serb Orthodox Church clergy — as victims of Albanians, Croats and Bosniaks, and sometimes even Montenegrins.

This resulted in the whitewashing of Milošević’s policies for which he was tried at The Hague, while the chance for the nation’s self-reflection was eventually wasted.

And in the end, the type of black-and-white thinking typical of populists everywhere has denied Serbia a shot at a complete catharsis.

The opposition long embraced victimhood, too

A more nuanced view would show that it is indeed quite possible to mourn the deaths of innocent Serbian civilians during the bombing and to admit that Milošević and his allies were war criminals who brought destruction to their neighbours and, ultimately, their own country.

No sane Serbian would welcome the bombing of his own country, but any moral and decent citizen of Serbia would have stopped supporting Milošević as it became clear he was waging yet another conflict.

And yet, while more than two decades later, some 80% of the voters in the 2022 election opted for populist or outright nationalistic parties, parts of Serbia’s more liberal and progressive opposition (as they claim to be) paradoxically also promote Milošević’s narratives.

For instance, Vuk Jeremić, the former foreign minister of Serbia and the leader of the centre-right Narodna stranka or "People’s Party," openly wrote on Twitter on 24 March that the NATO campaign was aimed against the Serbian nation and not against Milošević’s regime.

"If those are the liberal talking points, one can then easily imagine what the nationalist and far-right parties are saying."

Intentionally or not, he illustrated this statement with a photograph of Baghdad in flames.

Even Dobrica Veselinović, the leader of the green-liberal Ne da(vi)mo Beograd or "Do Not Let Belgrade D(r)own" political movement, started his tweet on the same day with a condemnation of the “NATO aggression”.

If those are the liberal talking points, one can then easily imagine what the nationalist and far-right parties are saying.

Ethnonationalism feeds on self-righteousness

Beyond the collective trauma that the bombing campaign brought to the nation’s psyche lies the foundation of ethnonationalism — the dominant ideology in Serbia, but also the rest of the region, since the 1990s.

The nature of ethnonationalism is that it disregards the interests or suffering of neighbouring nations and focuses solely on a singular, own “righteous” nation.

"This hypothesis ... gave the people what they wanted: a sense of superiority over their neighbours while retaining the angelic aura of innocence that comes with victimhood."

Through the lenses of Serbian ethnonationalists, ethnic Serbs have the right to secede from any other neighbouring country and form Greater Serbia.

Yet Albanians, Bosniaks, Hungarians, Romanians, Vlachs and Bulgarians, who all populate distinct regions of Serbia, have no such right, even if they are repressed at some point.

This hypothesis explains why Milošević’s narratives about Serbs as the only victims enjoyed and continue to enjoy such popularity.

After all, it gave the people what they wanted: a sense of superiority over their neighbours while retaining the angelic aura of innocence that comes with victimhood.

As a narrative, it's astonishingly myopic yet incredibly empowering: it simultaneously wholeheartedly supports aggression against the perpetual “other” and the feeling of being under constant existential threat by the same “other”.

The change has to come from within

The narrative in question is particularly resilient to outside change, and no amount of pressure from foreign democratic forces or factors can weaken it.

If anything, it cannot simply be displaced through foreign "carrot and stick" methods — as seen in the way Brussels has attempted to use the country's EU integration, for instance — because defeats, even when barely on the horizon, only further strengthen the feeling of victimhood.

"Forward-thinking, progressive Serbs must work together to find a way to bring their own society out of the depths of self-deluded ethnonationalism."

The only way out can be found from within. Forward-thinking, progressive Serbs must work together to find a way to bring their own society out of the depths of self-deluded ethnonationalism.

In this, they need and will need the support of the democratic world.