Renewal of cross-border aid mechanism promises little relief for war-displaced Syrians

After weeks of uncertainty, the council voted unanimously on Jan. 9 to renew the aid lifeline, allowing assistance to reach millions of people displaced by the conflict, which is now approaching its 12th year.

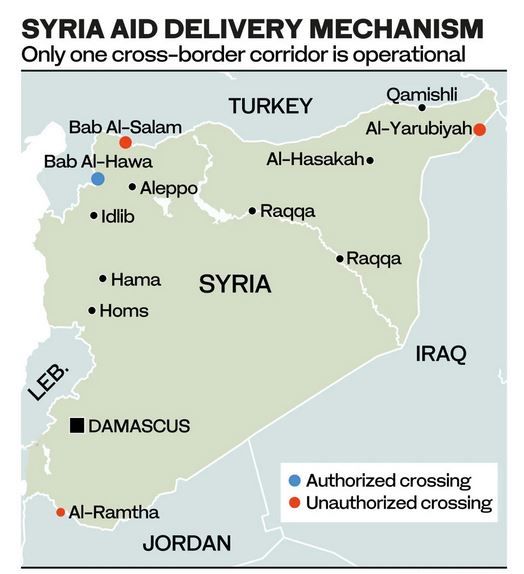

Just a day before the resolution was due to expire, the 15-member council agreed on an extension until July 10, permitting aid to be delivered across Turkyie’s border via the Bab Al-Hawa crossing.

The crossing provides more than 80 percent of the needs of people living in rebel-held areas and is the only way UN assistance can reach civilians without crossing areas controlled by the Bashar Assad regime.

Aid arrives at a camp for displaced Syrians.

Aid arrives at a camp for displaced Syrians. Although the renewal has been welcomed by aid agencies, many say the six-month extension is far too short to allow for a sustainable, meaningful and cost-effective humanitarian response.

“Shorter mandates contribute to a cycle of contingency planning, which limits our capacity to reach those who require assistance,” Nicola Banks, advocacy manager at the UK-based charity Action for Humanity, told Arab News.

“Humanitarian conditions are worsening, and agencies’ inability to plan ahead for longer than six months risks assistance that is less effective and more expensive.”

Medecins Sans Frontieres, which receives almost all of the supplies needed for its Syria response via the Bab Al-Hawa crossing, is also concerned about the limits imposed by the six-month renewal.

“Insecurity and access constraints continue to severely limit our ability to provide humanitarian assistance that matches the scale of the needs,” Sebastien Gay, MSF’s head of mission for Syria, told Arab News.

The capacity of aid agencies “to fulfill the needs of people, particularly food and health care, is being weakened by the prolonged economic crisis, hostilities and a general decrease of humanitarian funding over the years.

“Even with the cross-border mechanism in place, the need for humanitarian assistance and medical care in northwest Syria exceeds what is provided by humanitarian organizations.”

Inmates’ relatives wait outside a Damascus prison after an Assad regime crackdown.

Inmates’ relatives wait outside a Damascus prison after an Assad regime crackdown.

Gay said that the short-term renewal of the cross-border resolution has already created gaps for organizations operating in northwest Syria in the past year, limiting their ability to work on long-term projects and solutions to people’s needs.

According to a Security Council report published in December, just 18 percent of the $209.5 million needed for the winter response in Syria has been funded. This lack of certainty has forced agencies such as MSF to stretch their intervention.

“It is difficult to predict the future for the displaced people in northern Syria, especially while the conflict continues, and insecurity persists for this extremely vulnerable population,” he said.

“In the past two years, MSF has seen various health facilities and projects downscale their activities or close after losing their funds. Against this backdrop, MSF had to step up services to cover critical gaps.

“Downscaling those services endanger the lives of thousands of pregnant women and girls and their new-born children or lead to the spread of waterborne diseases, including cholera.”

After almost 12 years of civil war, about 1.8 million people now live in camps and informal settlements in Syria’s rebel-held northwest, according to the latest data from the UN Refugee Agency, with plummeting winter temperatures exacerbating already harsh conditions.

The camps were designed to act as temporary shelters, but tens of thousands of civilians fleeing violence now find themselves trapped in squalid, overcrowded sites with limited access to food, clean water, sanitation, healthcare and adequate shelter.

“Tents leak, the streets turn to mud, and freezing temperatures take a heavy toll on people’s physical and mental health,” Gay said.

Many families in the camps are living in the same canvas tents provided by aid agencies 10 years ago.

“The temperature inside and outside the tent is the same,” Hisham Dirani, CEO of the Violet Organization, a Syrian NGO, told Arab News. “This threatens the lives of children. Last winter, we witnessed children die due to the cold conditions at night.”

Along with the biting cold, the winter months bring a host of hazards, including respiratory diseases, waterborne infections, and even burns and complications caused by smoke inhalation due to improper heating methods.

Families with access to a stove and fuel are considered lucky. But even keeping warm can prove fatal, as fires occur “hundreds of times each winter,” said Dirani.

“Parents stay awake at night in anticipation of any emergency the kids may face, and keep the heater running by burning anything.”

In previous years, families burned wood, coal and pistachio shells to heat their tents. This year, amid a nationwide fuel shortage, even these basics have become scarce, leading many to burn trash and anything else they can find.

“Inhaling fumes from burning plastic, manure and coal is harmful and often results in children falling ill,” a spokesperson for the Hand in Hand for Aid and Development Foundation, a Syrian-British charity, said.

“The damp winter conditions, compounded by overcrowding and a lack of access to adequate sanitation, are likely to increase cases of respiratory infection, health issues from smoke inhalation and waterborne diseases.”

Hospitals operating near the camps “have recorded an increase in cases of bronchitis and lung damage in children,” the foundation’s spokesperson said.

“Without a proper response, this winter is likely to cause deaths from hypothermia or fires inside tents.”

Gay said that MSF medics treated 980 burn victims in northern Idlib last winter. In 2021 alone, 345 fires broke out in camps in the region, killing 12, injuring 61 and destroying 516 shelters, according to UNHCR.

Fires and noxious fumes are not the only threats facing camp communities over winter. Without sufficient drainage, sites are frequently flooded, destroying possessions, compounding cold conditions and breeding waterborne diseases.

According to the foundation spokesperson, storms and heavy rain destroyed more than 6,700 tents and damaged over 22,800 in camps across northwestern Syria.

Disease is also exacting a heavy toll. Idlib has recorded more than 14,000 suspected cholera cases and Aleppo more than 11,000 since the outbreak began in September, making the cities the second and fourth worst-hit in Syria, respectively.

Cold, hunger and inadequate shelter take a heavy toll on Syrian children in overcrowded camps

Cold, hunger and inadequate shelter take a heavy toll on Syrian children in overcrowded camps

These regions are particularly vulnerable because they rely on polluted water from the Euphrates River to drink and irrigate crops, and because the health sector in rebel-held Syria has been battered by more than a decade of war.

It is not just the physical toll of these conditions that concern humanitarian aid agencies. Years of uncertainty, poor living conditions and untreated psychological trauma have created a mental health crisis among the displaced.

According to HIHFAD, there were 83 suicides in the camps between early 2021 and mid-2022.

Unless funding targets are met by donor nations and access via Bab Al-Hawa is guaranteed for longer than six months at a time, aid agencies warn they will lack the capacity to save lives and ease suffering in northern Syria.

“We continue to call for a 12-month mandate, and hope a 12-month mandate will be the subject of future discussions,” Banks, of Action for Humanity, told Arab News.

This would enable aid agencies to scale up their response with the predictable, long-term support needed, she said.