Explained: Why the French President’s visit to Lebanon matters

In his second visit to Lebanon since the Beirut explosion, French President Emmanuel Macron on Tuesday – exactly 100 years after the West Asian nation was founded by colonial France – gave Lebanese politicians an ultimatum to bring in reforms by the end of October, saying that bailout funds would be blocked and targeted sanctions imposed in cases of proven corruption.

Macron arrived on a two-day visit Monday, hours after Mustapha Adib, a little-known diplomat, was designated as Lebanon’s new Prime Minister under pressure from France.

Macron’s second visit

Lebanon in the recent past has been crippled by serious economic woes at the centre of which has been a currency crisis. This has caused large-scale closure of businesses and soaring prices of basic commodities resulting in social unrest. Damage from the blast alone, estimated at $8 billion, has added to the country’s problems.

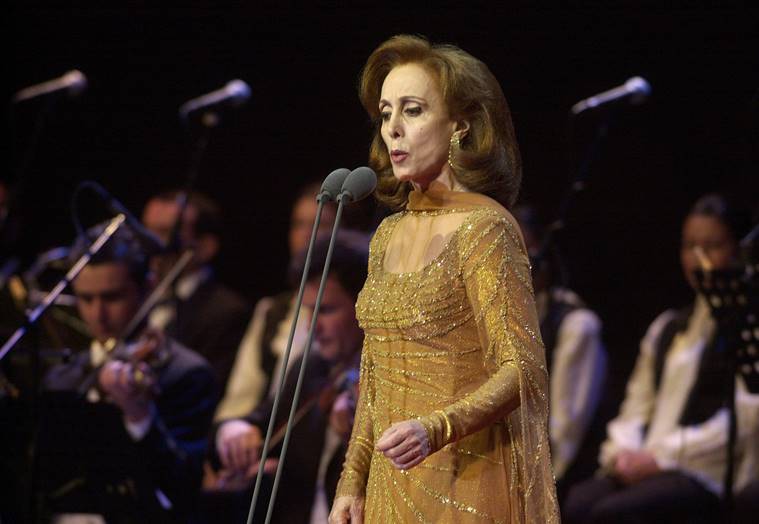

After arriving Monday, Macron formally met Fairouz, a singer who is considered a unifying figure in the country, before meeting political figures largely reviled by the public.

On Tuesday, Macron said he wanted to usher in a “new political chapter” and warned that financial assistance to the country was not a “blank cheque”, saying: “If your political class fails, then we will not come to Lebanon’s aid.”

Visiting Beirut’s port, Macron said France would help organise a second international aid conference with the United Nations in October, after the first made commitments worth $298 million for disaster relief.

Macron has asked for “credible commitments” from Lebanese political leaders, which include an audit of the country’s central bank, and that parliamentary elections be held in six to 12 months.

The French leader has also threatened the use of targeted sanctions, should Lebanon’s ruling class not bring in real change in the next three months.

Why the visit carries weight

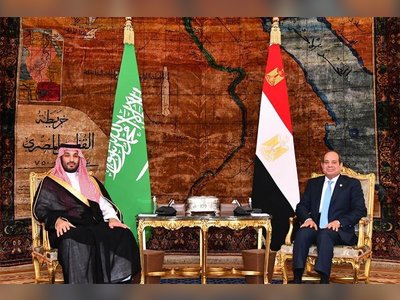

The multiple visits by Macron come at a time when the region’s traditional powers, Saudi Arabia and the United States, have taken a back seat. France is now trying to fill this vacuum, experts say.

Also, the emotional bond that many Lebanese continue to feel for their past colonial ruler helps France take a more active role — its influence clearly visible after Macron’s second tour of the country in four weeks.

When nationwide protests last year caused the ouster of Saad Hariri, Lebanon’s prime minister at the time, his successor Hassan Diab took three months to form a new government, which then lasted barely six months as Diab resigned soon after the Beirut blast. Even after the catastrophic explosion, Lebanese politicians struggled to decide who the next prime minister would be.

The situation changed dramatically under direct French pressure, and on August 31, just before Macron’s visit, Mustapha Adib became prime minister with the support of 90 out of the nation’s 120 parliamentarians.

During his visit, Macron has also expressed support for an overhaul of the current sectarian arrangement between Lebanon’s Shiites, Sunnis and Christians, known for its long periods of political gridlock, and for bringing in a new “political pact” that would have a greater civil footing. He has promised his next visit to the country in December.